American Folk Singer Pete Seeger Dies

Pete Seeger, the banjo-picking troubadour who sang for

migrant workers, college students and star-struck presidents in a career that

introduced generations of Americans to their folk music heritage, died on

Monday at the age of 94.

Seeger's grandson, Kitama Cahill-Jackson said his

grandfather died at New York Presbyterian Hospital, where he'd been for six

days. "He was chopping wood 10 days ago," he said.

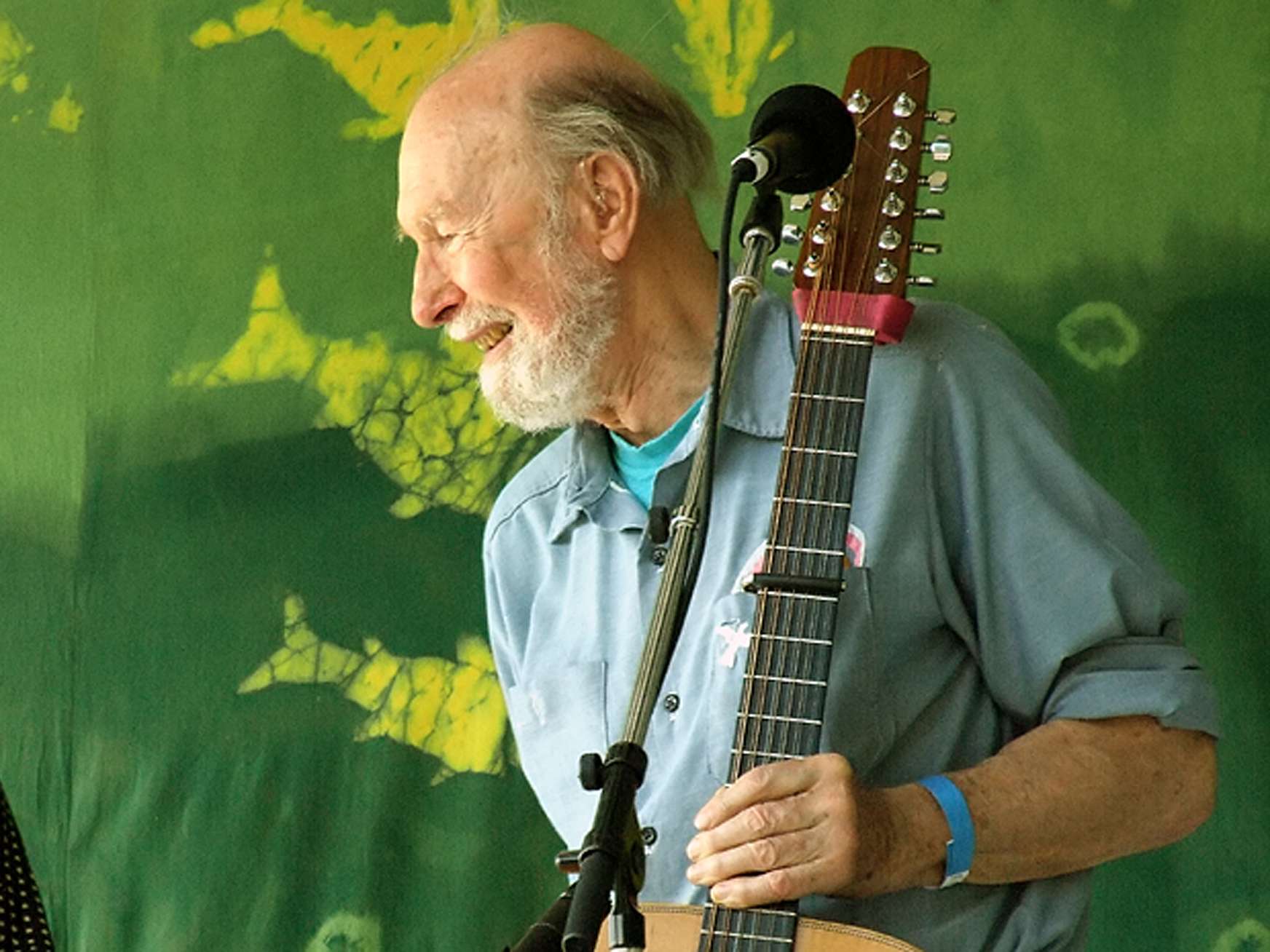

Seeger — with his a lanky frame, banjo and full white beard

— was an iconic figure in folk music. He performed with the great minstrel

Woody Guthrie in his younger days and marched with Occupy Wall Street

protesters in his 90s, leaning on two canes. He wrote or co-wrote "If I

Had a Hammer," ''Turn, Turn, Turn," ''Where Have All the Flowers

Gone" and "Kisses Sweeter Than Wine." He lent his voice against

Hitler and nuclear power. A cheerful warrior, he typically delivered his

broadsides with an affable air and his banjo strapped on.

"Be wary of great leaders," he told The Associated

Press two days after a 2011 Manhattan Occupy march. "Hope that there are

many, many small leaders."

With The Weavers, a quartet organized in 1948, Seeger helped

set the stage for a national folk revival. The group — Seeger, Lee Hays, Ronnie

Gilbert and Fred Hellerman — churned out hit recordings of "Goodnight

Irene," ''Tzena, Tzena" and "On Top of Old Smokey."

Seeger also was credited with popularizing "We Shall

Overcome," which he printed in his publication "People's Song,"

in 1948. He later said his only contribution to the anthem of the civil rights

movement was changing the second word from "will" to

"shall," which he said "opens up the mouth better."

"Every kid who ever sat around a campfire singing an

old song is indebted in some way to Pete Seeger," Arlo Guthrie once said.

His musical career was always braided tightly with his

political activism, in which he advocated for causes ranging from civil rights

to the cleanup of his beloved Hudson River. Seeger said he left the Communist

Party around 1950 and later renounced it. But the association dogged him for

years.

He was kept off commercial television for more than a decade

after tangling with the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1955.

Repeatedly pressed by the committee to reveal whether he had sung for

Communists, Seeger responded sharply: "I love my country very dearly, and

I greatly resent this implication that some of the places that I have sung and

some of the people that I have known, and some of my opinions, whether they are

religious or philosophical, or I might be a vegetarian, make me any less of an

American."

He was charged with contempt of Congress, but the sentence

was overturned on appeal.

Seeger called the 1950s, years when he was denied broadcast

exposure, the high point of his career. He was on the road touring college

campuses, spreading the music he, Guthrie, Huddie "Leadbelly"

Ledbetter and others had created or preserved.

"The most important job I did was go from college to

college to college to college, one after the other, usually small ones,"

he told The Associated Press in 2006. " ... And I showed the kids there's

a lot of great music in this country they never played on the radio."

His scheduled return to commercial network television on the

highly rated Smothers Brothers variety show in 1967 was hailed as a nail in the

coffin of the blacklist. But CBS cut out his Vietnam protest song, "Waist

Deep in the Big Muddy," and Seeger accused the network of censorship.

He finally got to sing it five months later in a stirring

return appearance, although one station, in Detroit, cut the song's last

stanza: "Now every time I read the papers/That old feelin' comes on/We're

waist deep in the Big Muddy/And the big fool says to push on."

Seeger's output included dozens of albums and single records

for adults and children.

He also was the author or co-author of "American

Favorite Ballads," ''The Bells of Rhymney," ''How to Play the

Five-String Banjo," ''Henscratches and Flyspecks," ''The Incompleat

Folksinger," ''The Foolish Frog" and "Abiyoyo," ''Carry It

On," ''Everybody Says Freedom" and "Where Have All the Flowers

Gone."

He appeared in the movies "To Hear My Banjo Play"

in 1946 and "Tell Me That You Love Me, Junie Moon" in 1970. A reunion

concert of the original Weavers in 1980 was filmed as a documentary titled

"Wasn't That a Time."

By the 1990s, no longer a party member but still styling

himself a communist with a small C, Seeger was heaped with national honors.

Official Washington sang along — the audience must sing, was

the rule at a Seeger concert — when it lionized him at the Kennedy Center in

1994. President Clinton hailed him as "an inconvenient artist who dared to

sing things as he saw them."

Seeger was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in

1996 as an early influence. Ten years later, Bruce Springsteen honored him with

"We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions," a rollicking

reinterpretation of songs sung by Seeger. While pleased with the album, Seeger

said he wished it was "more serious." A 2009 concert at Madison

Square Garden to mark Seeger's 90th birthday featured Springsteen, Dave

Matthews, Eddie Vedder and Emmylou Harris among the performers.

Seeger was a 2014 Grammy Awards nominee in the Best Spoken

Word category, which was won by Stephen Colbert.

Seeger's sometimes ambivalent relationship with rock was

most famously on display when Dylan "went electric" at the 1965

Newport Folk Festival.

Witnesses say Seeger became furious backstage as the

amped-up band played, though just how furious is debated. Seeger dismissed the

legendary tale that he looked for an ax to cut Dylan's sound cable, and said

his objection was not to the type of music but only that the guitar mix was so

loud you couldn't hear Dylan's words.

Seeger maintained his reedy 6-foot-2 frame into old age,

though he wore a hearing aid and conceded that his voice was pretty much shot.

He relied on his audiences to make up for his diminished voice, feeding his

listeners the lines and letting them sing out.

"I can't sing much," he said. "I used to sing

high and low. Now I have a growl somewhere in between."

Nonetheless, in 1997 he won a Grammy for best traditional

folk album, "Pete."

Seeger was born in New York City on May 3, 1919, into an

artistic family whose roots traced to religious dissenters of colonial America.

His mother, Constance, played violin and taught; his father, Charles, a

musicologist, was a consultant to the Resettlement Administration, which gave

artists work during the Depression. His uncle Alan Seeger, the poet, wrote

"I Have a Rendezvous With Death."

Pete Seeger said he fell in love with folk music when he was

16, at a music festival in North Carolina in 1935. His half brother, Mike

Seeger, and half sister, Peggy Seeger, also became noted performers.

He learned the five-string banjo, an instrument he rescued

from obscurity and played the rest of his life in a long-necked version of his

own design. On the skin of Seeger's banjo was the phrase, "This machine

surrounds hate and forces it to surrender" — a nod to his old pal Guthrie,

who emblazoned his guitar with "This machine kills fascists."

Dropping out of Harvard in 1938 after two years as a

disillusioned sociology major, he hit the road, picking up folk tunes as he

hitchhiked or hopped freights.

"The sociology professor said, 'Don't think that you

can change the world. The only thing you can do is study it,'" Seeger said

in October 2011.

In 1940, with Guthrie and others, he was part of the Almanac

Singers and performed benefits for disaster relief and other causes.

He and Guthrie also toured migrant camps and union halls. He

sang on overseas radio broadcasts for the Office of War Information early in

World War II. In the Army, he spent 3½ years in Special Services, entertaining

soldiers in the South Pacific, and made corporal.

Pete and Toshi Seeger were married July 20, 1943. The couple

built their cabin in Beacon after World War II and stayed on the high spot of

land by the Hudson River for the rest of their lives together. The couple

raised three children. Toshi Seeger died in July at age 91.

The Hudson River was a particular concern of Seeger. He took

the sloop Clearwater, built by volunteers in 1969, up and down the Hudson,

singing to raise money to clean the water and fight polluters.

He also offered his voice in opposition to racism and the

death penalty. He got himself jailed for five days for blocking traffic in

Albany in 1988 in support of Tawana Brawley, a black teenager whose claim of

having been raped by white men was later discredited. He continued to take part

in peace protests during the war in Iraq, and he continued to lend his name to

causes.

"Can't prove a damn thing, but I look upon myself as

old grandpa," Seeger told the AP in 2008 when asked to reflect on his

legacy. "There's not dozens of people now doing what I try to do, not

hundreds, but literally thousands. ... The idea of using music to try to get

the world together is now all over the place."

No comments:

Post a Comment